The Ghost of My Grandfather – Oaxaca, 1992

It was 1992, in Oaxaca, Mexico. As i already mentioned in my first blog after receiving an invitation from my mother’s mother, (my abuelita) our family decided to visit her in Mexico for what she called a “Much needed reunion .” That summer was spent meeting our entire extended family on both my father’s and mother’s sides. Most of them I had never met, but they were eager to meet us. This Story is about my other grandfather My mothers father, (my abuelito).

We lived in New York, born and raised—except for my older sister Iris. We were the first generation born in America, and there was a lot of excitement surrounding our trip to Mexico. I’m sure there were high expectations and plenty of curiosity from relatives who had long wondered, “How is that part of the family doing in New York? What is New York like?”

So many family members were aware of our visit that summer that a decision was made to divide our time evenly—half with my father’s side of the family, and half with my mother’s. In a previous post, I talked about my grandfather on my father’s side, the first time I ever held a Coca-Cola glass bottle. But this story is different. This one is about the spirit, or ghost, of my mother’s father.

The story begins inside my mother’s childhood home, where we went to visit her side of the family. I was nine years old at the time, and I found the trip to Mexico extremely difficult for several reasons, mainly because I was, in every sense, a spoiled first-world American kid.

I was used to water that tasted clean and refreshing. The water in Mexico did not. I was used to food prepared a certain way, and the meals there tasted entirely different. The milk, the meats, even the oils they used to cook. Everything tasted foreign, and it took time to adjust. We were there for quite a while, at least four months, from June through October, living and interacting daily with our relatives.

Because I was the main complainer in my family (that was visting). I quickly earned a reputation as the troublemaker, even the crybaby. My youngest sister hadn’t been born yet; she wouldn’t arrive until 1995. But back then, my mother and sisters never complained about the food, the atmosphere, or the rules about bedtime and daily routines.

Still, I couldn’t help but protest. I ask you, if you took anyone away from a comfortable life, full of good food and clean water, and placed them in a setting of hardship and scarcity, wouldn’t they notice? Wouldn’t they complain? I know I did.

At nine years old, I didn’t fully understand what I was experiencing, but looking back, I call it the spoiled American effect. Having constant access to clean water and a high quality of life creates a giant perspective shift when it’s suddenly taken away.

Throughout the days, I had fun playing with my cousins and the other kids around the neighborhood. It was an amazing feeling to be free in such wide-open country, surrounded by hills, rocky terrain, and mountains where goats and other animals roamed freely.

I remember watching my abuelita, my mother’s mother, roasting a pot of soup in a small house separated from the main house. It was designed that way to prevent fires from spreading, a kind of outdoor kitchen. Inside, she kept an old couch where she would sometimes sleep beside the simmering pot.

One day, I walked into that room and saw her asleep next to the soup. “Grandma, what are you doing?” I asked.

She woke slightly and said, “What do you think I’m doing? I’m making sure this pot of soup gets cooked right.”

She stirred it once or twice, then lay back down again. I didn’t think much of it at the time. I just assumed old people had their own reasons for being grumpy and went about my business.

Her backyard was beautiful, a patchwork of wildflowers and a full-grown lime tree. Each section of plants was encircled by small stones, forming a homemade garden that looked both natural and intentional.

I remember walking along those stones when one of them wobbled. Something underneath caught my attention. I bent down, lifted the rock, and a swarm of enormous roly-poly bugs scattered in every direction. They rushed beneath other rocks to hide. I had never seen roly-polies that big before. I was used to the tiny ones in New York, but these Mexican bugs were huge and strangely fascinating.

On another occasion, one of my aunts, her name was Ruby, had a visitor. She was in her mid-twenties at the time, and the man who stopped by was clearly an admirer. He arrived with the most unusual thing I’d ever seen: an exotic animal on a leash.

The creature was hard to describe. Over the years, as we retold the story, we decided it must have been a very large anteater.

The man said he had come by to show my aunt the animal, though everyone could tell he was really there to see her. When we told him she wasn’t home (which wasn’t true, she had purposely locked herself in her room and whispered, “Just tell him I’m not here”), he smiled politely and said he’d be on his way soon because his animal was hungry.

We tried to offer the anteater some leftover chicken and rice, but the man stopped us quickly. “Please don’t feed him that,” he said. “It’ll make him sick. He only eats bugs.”

“Bugs?” I repeated.

“That’s right,” he said. “Just bugs.”

Immediately, I remembered the garden. “Hey, I know where there’s tons of bugs!” I told him. My older sister and one of our cousins ran out with me to the backyard, where we started flipping over the rocks around my grandmother’s garden.

When the anteater saw what was underneath, it went wild with excitement. It ate the bugs like a vacuum, its long tongue darting in and out as it cleared the ground. It was mesmerizing to watch. The animal seemed completely content.

The man stayed for maybe fifteen or twenty minutes, chatting with us while his anteater feasted. Then he thanked us and went on his way.

What an amazing experience that was. Even now, we all still remember that day and smile.

Before I continue, I should explain the layout of the house. From the street, one corner of it held my grandmother’s small store. She sold soft drinks, snacks, and various small items from that corner of her home. On the same side was the living room. That part of the house was clearly divided, the storefront on one end, the living quarters on the other.

From the living room, a small hallway ran deeper into the house. Two beds were set up along that hallway, and at the end of it was the kitchen area, not to be confused with the cooking area, which was separate. Next to the kitchen was my grandparents’ old bedroom, where we stayed during our visit.

The room had a large king-sized bed in the center, and along the far wall stood a big dresser or armoire where they kept their clothes. At the foot of the king bed sat a single chair in the corner. So if you walked into the room, you’d see the large bed, a smaller twin bed, the armoire along the wall, and a small window at head height.

That window was important, because each night, a candle would burn there. I refused to sleep in total darkness. There were no fans, no sounds, just silence and blackness. It was impossible for me to sleep that way. For the first few nights, we endured it, but eventually, I complained enough that my mother bought candles to keep a dim light glowing while we slept.

Next to the kitchen was a path that led outside. The restroom and shower were not attached to the house, you had to walk all the way through the backyard to reach them. At the very back stood a small outhouse structure that served as both the bathroom and the shower area. Nearby was a laundry section, where running water flowed over a concrete wash shelf with a drain. There were no washers or dryers, everything was done by hand. Clothes were scrubbed with soap and water, beaten against stone, and then hung to dry on clotheslines under the sun.

Between the outhouse and the main house was another small structure, a shack where my grandmother cooked. Inside was a fire pit and a few blackened pots that simmered and boiled day after day.

One of the hardest parts of my stay in Mexico was the food, but an equally difficult part was nighttime. Being nine years old meant I had zero say in what time I went to bed or woke up. Once the sun went down, there wasn’t much to do. My grandmother didn’t own a television, and of course, we had no cell phones or laptops, this was 1992.

So by 9 p.m., everyone was going to sleep. The house fell silent. There was no light except for our candles.

In our room, my big sister slept on one side of the king bed and I was on the other, because, heaven forbid if she accidentally touched or cuddled me, she acted like it was the worst thing in the world. I suppose most sisters are like that. On the twin-sized bed, my mother slept beside my little sister Jennifer, who was born in 1989. That would make her only four years old at the time.

The Night I Saw My Grandfather’s Ghost

And so, on one particular night, as 9 p.m. drew near, everyone made their way to their rooms. My aunt went to hers, my uncle to his, and my mother, sisters, and I went to ours. Just like every night, my mom lit the candle, helped us into bed, and we all lay down.

Even now, as a forty-two-year-old adult, I still find it difficult to fall asleep at night. I’ve never been good at it. And on this one particular night, after everyone else had drifted off, I stayed awake, staring at the ceiling, thinking about the things nine-year-olds think about, looking forward to the next day.

The candlelight flickered softly on the window ledge, its glow swaying and dancing against the walls. I don’t know how much time had passed since we went to bed, but at some point, I looked down toward my feet—toward the corner next to the clothing cabinet where the lone chair sat.

That’s when I saw it.

A clear silhouette of a man was sitting there.

There was only one way in and out of that room, and I would have seen if anyone had entered. But I hadn’t. I lay there, frozen, not knowing what to do. At first, I tried to ignore it, convincing myself that maybe one of my uncles had come in to sit quietly, perhaps enjoying the comfort of family being together again.

But the longer I stared, the more details I began to see, and the less sense it made. The figure didn’t move. Slowly, the silhouette took shape: a face, hands, the outline of a formal suit. I could even make out the pinstripes on the fabric and the shine of his shoes.

I tried my hardest to reach over and tap my sister to wake her up, but she was too far away. I whispered, “Iris… Iris… wake up. Do you see, who is that sitting in the chair at the foot of the bed? Is that our uncle?”

Nothing. Silence.

I looked over to my left and saw my mom and little sister sleeping soundly. The stillness in the room was heavy. “Mom… Mom, are you awake?” I whispered. “Mom, wake up.” Still no answer.

I must have laid there for ten, maybe twenty minutes, covers pulled up to my chin, staring up at the ceiling and trying to convince myself it was nothing. Maybe it’s just one of my uncles, I thought. Maybe it’s normal here. Mexico has different customs. Maybe someone just came in to check on us.

But as I rustled in bed, unable to sleep, I finally sat up and rubbed my eyes. When I looked again, the man was still there. Clear as day.

I wasn’t half-asleep or seeing things. I was wide awake.

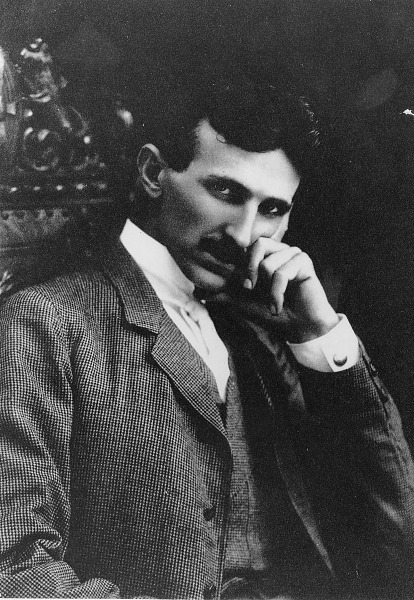

The man sat perfectly still, one leg crossed over the other, his right hand holding up his head as if he were deep in thought. He never looked at me. He just stared toward my mother. His fingers partly covered his face, but I could see the outline of a thin mustache, slick dark hair combed neatly back, and a look of deep, quiet reflection.

I whispered again, “Uncle? Is that you? Who are you?”

No response.

He just sat there calm, motionless, thoughtful.

I stared for what felt like forever, then finally pulled the covers over my face. After more whispering and failed attempts to wake my family, I shot up, jumped over my sister and mother’s bed, and ran out of the room.

I looked back once before leaving. The man was still there, sitting exactly as before, staring at my mother.

I ran straight to my uncle’s room and asked if I could sleep there. He smiled and said, “Of course, come in.” He handed me a small stack of comic books old, newspaper-style cartoons and I sat up reading them until I finally drifted off to sleep.

The next morning, during breakfast, I told my mom about the “strange custom” I thought existed in Mexico, how people might sit in a room and quietly watch others sleep. She stopped what she was doing mid-motion and said, “What are you talking about?”

I described everything—the man’s appearance, the fine pinstriped suit, the slicked-back hair, the mustache, the polished shoes, and the exact chair he was sitting in.

My mother didn’t say a word. She stood up, left the room, and came back with an old photograph.

She placed it in front of me and asked, “Is this who you saw?”

I looked at it and felt my chest tighten. “Yes,” I said. “That’s him exactly. Why was he here?”

My mother’s eyes softened. “That’s my father,” she said quietly. “And that was his chair. That dresser with the clothes, you were sleeping in his room. He died many years ago.”

I just stared at her. “What did you say? He’s dead? Then… I saw a ghost?”

Without much hesitation, she replied, “Obviously, he came back to see us. I haven’t been here in so long. He died when I was a teenager. He must have come one last time to visit.”

Her words were calm, even a little proud. She was sad that it hadn’t been her who saw him.

After that day, I never slept in that room again. I stayed with my uncle instead. I wanted no part of that situation.

But as I grew older, I often thought back to that night, and to the man sitting so still in deep thought. Years later, as I began reading about famous scientists, I became the biggest fan of Nikola Tesla and his unfinished works. And when I came across his portraits, I realized something strange: in many of his most famous photographs, Tesla sits in the exact same posture, one leg crossed, head resting on his hand, lost in thought.